美国近日对委内瑞拉的突袭行动,将总统尼古拉斯·马杜罗从本国强行带走,已被白宫描述为一次“跨国执法行动”。然而,这一叙事难以掩盖其本质——从国际法角度审视,该行为已明显构成国家间“使用武力”,而远非执法协助或司法引渡的范畴。此次行动包含对外国军事目标的打击、造成人员伤亡,并在未经当事国同意的情况下拘押一国在任元首,已然触及国际法体系中最根本、最严格的禁止领域。

这标志着一种深刻的制度性断裂:从基于规则的多边主义承诺,滑向凭借实力自行其是的“武力时代”。尤为严重的是,此次行动构成对《联合国宪章》核心支柱的直接冲击。宪章第2条第4款明确禁止任何国家对他国领土完整或政治独立使用或威胁使用武力,而本次突袭既非边境执法,也缺乏当事国同意,是典型的跨境武力行为。同时,宪章第39至42条将授权集体军事行动的专属权力赋予联合国安理会,第51条则仅在“武装攻击”发生时才例外允许自卫——本案中,这两项前提均不存在。行动本身,已构成对战后国际秩序法律基石的公然挑战。

除条约法义务外,此次行动亦侵蚀了国际习惯法中长期屹立的两大基石:国家主权原则与不干涉内政原则。国际法院在具有里程碑意义的“尼加拉瓜诉美国案”中早已阐明,未经同意对他国采取军事或准军事行动,即构成对此类基本原则的违反。国际法的保护并不因一国政府的内外政策而有所区别;其根本目的,正是为防止强权以“好恶”之名,行干涉之实。

即便从美国国内宪政框架审视,此次行动也疑云重重。1973年《战争权力法》明确规定,总统在动用武装力量后须在48小时内向国会通报,持续超过60天的行动则必须获得国会明确授权。目前公开信息中未见履行这些关键程序的证据。若情况属实,这不仅可能构成对国内法的违背,更深层次上,将进一步削弱国会在战争与和平问题上的宪法角色,冲击三权分立的制衡根基。

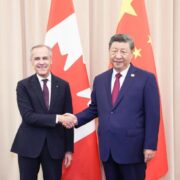

在这一背景下,加拿大及其他中等强国的立场,便具有超越个案的国际制度意义。问题的核心,并非是对特定政权的认可与否,而在于国际法律秩序的基本强制力是否得以维系。历史表明,国际秩序无法仅凭大国意志运转;它尤其依赖中等强国在多边框架内持续提供合法性、规范压力与制度惯性。当大国选择绕开规则,而小国无力制衡时,中等力量国家的集体声音与选择,便成为决定秩序走向的关键变量。

当前趋势,正将世界推向《华盛顿邮报》所警示的“地缘政治狂野西部”。在这一图景中,武力的使用不再需要严谨、事前的法律正当性论证,转而依赖于事后的政治包装与叙事塑造。从法律视角看,这预示着国际社会曾视若珍宝的禁止使用武力原则,正面临从不容贬损的强行法退化为可被选择性忽视的规范的危险。

因此,对于加拿大及与其类似的中等强国而言,此刻的沉默将是昂贵的。它们无须与任何大国对抗,但必须为规则清晰发声。坚持法律的底线,捍卫规范不可替代的权威,是其不可推卸的“制度守门人”职责。国际秩序的生命力,从不取决于最强行为体的一时意愿,而在于是否始终有足够多的国家,愿意为维系共同规则承担切实的政治成本。

国际法不会自我执行。它的力量与生机,始终有赖于国家——尤其是那些承上启下的中等强国——持续不断的信念与践行。